- Home

- Denise Deegan

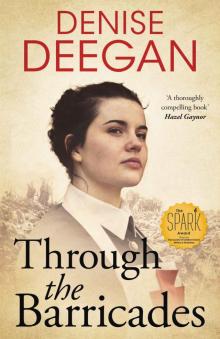

Through The Barricades: Winner of the SCBWI SPARK Award 2017

Through The Barricades: Winner of the SCBWI SPARK Award 2017 Read online

THROUGH THE BARRICADES

Denise Deegan

Copyright © Denise Deegan 2016

This first e-book edition published 2016.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted, in any form or by any means without the prior written permission of the author, nor be otherwise circulated in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition being imposed on the purchaser. This book is a work of fiction and, except in the case of historical fact, any resemblance to persons living or dead is coincidental. The right of Denise Deegan to be identified as the Author of the Work has been asserted by her in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

BY THE SAME AUTHOR

The Butterfly Novels:

And By The Way (US version)

And For Your Information (US version)

And Actually (US version)

The Butterfly Novels: Boxset (US version)

As Aimee Alexander:

The Accidental Life of Greg Millar

Pause to Rewind

All We Have Lost

Checkout Girl

Find all Denise Deegan titles on Amazon.com

Find all Aimee Alexander titles on Amazon.com

For news of offers & new books, sign up here - and receive a free copy of Checkout Girl when you do!

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Denise Deegan lives in Dublin with her family where she regularly dreams of sunshine, a life without cooking and her novels being made into movies. She has a Masters in Public Relations and has been a college lecturer, nurse, china restorer, pharmaceutical sales rep, public relations executive and entrepreneur. Denise's books have been published by Penguin, Random House, Hachette and Lake Union Publishing. Denise writes contemporary family dramas under the pen name Aimee Alexander. They have become international best-sellers on Kindle.

www.denisedeegan.com

CONTENTS

Go to the beginning

Part One

Part Two

Part Three

Part Four

To my very great friend, Maruja Bogaard,

with love, laughter and lilies

Prologue

1906

Maggie woke coughing. It was dark but there was something other than darkness in the air, something that climbed into her mouth, scratched at her throat and stole her breath. It made her eyes sting and tear. And it made her heart stall. Flames burst through the doorway like dragon breath. Maggie tried to scream but more coughs came, one after the other, after the other. She backed up in the bed, eyes wide, as the blaze began to engulf the room. She thought of her family, asleep in their beds. She had to waken them – with something other than her voice.

She hurried from her bed, peering through flame-lit smoke in search of her jug and washbasin. Reaching them, she flung water in the direction of the fire and began to slam enamel against enamel, fast and loud. She had to back away as flames lapped and roared and licked at her. But she kept on slamming.

Her arms grew tired. Her breath began to fail her. And she felt the heavy pull of sleep. She might have given in had she been alone in the house. But there was her father. There was her mother. There was Tom. And there was David. She could not give up.

Then like a miracle of black shadow, her father burst through the flames, his head tossing and turning. His frenzied gaze met hers.

‘Maggie!’

She began to cry with relief but relief changed to guilt as she realised that she had only drawn him further into the fire.

‘No! You were meant to take the stairs. You were meant to-’

‘It’s all right, Maggie Mae. It’s all right,’ he said, hurrying to her. He scooped her up and held her tight as he carried her away from a heat that burned without touching.

She felt cool air on her back as he opened the window. Wind rushed in, blowing the drapes aside. The flames roared louder, rose higher. But her father only looked out at the night sky. And down.

‘Missus O’Neill! I’m dropping Maggie down to you!’ he called. ‘Catch her now, mind. Catch my little girl.’ Then he looked deep into Maggie’s eyes. ‘Missus O’Neill is down below with her arms out for you. I’m going to drop you down to her.’

‘Will she catch you too?’

But he just smiled and kissed her forehead. ‘Make a difference in the world, Maggie.’

The sadness in his eyes filled her with a new terror. ‘But you’re coming too?’

He smiled once more. ‘I am, as soon as I get the others out. Now keep your eyes on mine, Maggie Mae. Keep your eyes on mine all the way down.’

part one

one

Daniel

October 1913

Daniel’s back stung from the rake of a rugby boot. What bothered him, though, as he cycled home, was how he had played. If he did not improve, he would lose his position on the team.

‘It’s too peaceful out here by far,’ said his friend, Michael, beside him. ‘You’d hardly know there was rioting in the city.’

‘Will we cycle in and have a look?’

‘I value my life too much,’ Michael said.

‘Is it that bad?’

‘I was referring to my father. He’d kill me if he found me anywhere near the trouble. He was clocked on the head with a rock last night while trying to control the mob.’

‘Is he all right?’

‘Ah. It’d take more than a rock to bring him down.’

Daniel knew little about these riots – apart from the fact that strikers had started them. ‘Why-’ he began but was cut off by Michael, calling out.

‘Behold! A damsel in distress!’

On the pavement, a girl was pushing her bicycle towards the city, bent forward as if in battle with life. Her front tyre was flat.

Daniel smiled at Michael’s transformation into a gallant knight. If he’d had a cape he’d have thrown it over a puddle – had there been a puddle. Instead, he flung his leg over his saddle and glided on one pedal to a halt beside her. Daniel had a feeling this would not end well.

‘I’m not in distress; I simply need a bicycle pump,’ the girl said. Wisps of black hair escaped her hat. Green eyes flashed impatience. She’d stopped but wouldn’t remain so for long.

Michael turned to him. ‘Daniel, a pump?’ Three words demoted him to able assistant.

‘A pump may not do it,’ Daniel said, promoting himself to bicycle expert. ‘How fast did the air go out?’ he asked the girl while fetching the pump from his schoolbag.

She put out her hand for it.

‘I’m already dirty,’ he said, holding on to it.

‘I’m not afraid of dirt.’

He felt suddenly that there was nothing this girl was afraid of. ‘Still. I could do with the exercise.’

Michael rolled his eyes.

The girl raised a cynical eyebrow.

Daniel ignored them both, taking the bicycle, propping it up against a lamppost and attaching the tube.

‘Allow me to introduce myself,’ Michael said to the girl with a flamboyant wave of his arm.

‘Must I?’ she asked.

Daniel smiled as he began to pump.

But Michael seemed encouraged. ‘So, where are you off to, anyway, in such a hurry?’

‘I have business to attend to in the city.’ She looked at Daniel impatiently.

‘Business, no less.’ Michael sounded amused. ‘Why don’t you take the tram? Here’s one now.’

It was rounding a corner, flanked by six large

policemen, all dressed in black, glancing around as if looking for trouble, encouraging it, almost.

‘I’m boycotting the trams in sympathy with Dublin’s strikers,’ she declared with sudden passion.

Daniel looked up.

‘You’re on the side of the strikers?’ Michael exclaimed as if he’d been prodded in the eye by a hot poker.

‘Why does that surprise you – because I attend a posh school like yours?’ She eyed his uniform with disdain.

‘Because they’re turning the city upside down!’ he insisted.

‘I’m sorry that, in demanding fairness, they are inconveniencing you.’ She sounded the opposite.

‘My father is with the police, so yes, it is an inconvenience, knowing that he has to face rioting thugs on a daily basis.’

‘It’s the police who are the thugs!’

Michael’s voice rose. ‘They are upholding law and order. The strikers are a mob of hooligans, too lazy to work.’

‘Lazy? They’ve been locked out by their employers!’

‘As they deserve to be, following that rabble-rouser, James Larkin, like clueless sheep.’

She moved like some kind of beautiful lightning, rising up into the air, her fist connecting with Michael’s chin, knocking him off balance and onto the ground. Her hat fell back.

She was a vision.

He was Daniel’s best friend.

‘I’m fine,’ Michael barked when Daniel went to help him up.

Daniel turned. Already, she was releasing the pump. She slammed it into his palm and mounted her bicycle. She took off like an angry wind.

‘Lunatic!’ Michael called after her, dusting himself off.

Daniel watched her disappear. It was like witnessing a flame go out. He had never met anyone more alive. She was fire and rage and passion and earnestness. No one he knew paid any attention to the strikers bar Michael whose father was involved. No one cared. And then this fireball arrives, taking their side, discarding gentility in favour of passion – passion for strangers and politics and fairness. She left him breathless.

He and Michael mounted their bicycles and resumed their journey in silence. But Daniel’s mind was full of her.

‘She’d a great face, though, all the same, hadn’t she?’ Michael said.

Daniel smiled. In fairness to his friend, he always bounced back.

‘I wouldn’t mind seeing that black hair of hers falling down over her shoulders,’ he continued.

‘Give over,’ Daniel said, though he knew that she would neither want nor need him to jump to her defence. ‘Who is this James Larkin chap anyway?’ he asked casually. Now, more than ever, he wanted an education on the strikers.

‘Ah God, Danny. You must know-’

‘Just tell me.’

‘James Larkin brought unions to Dublin. Without him workers would never have thought to band together and strike for better conditions.’

‘Perhaps they need better conditions,’ Daniel suggested, unable to clear his mind of her.

Michael gave him a withering look. ‘Tosh.’

Daniel said nothing.

‘The strikes have brought nothing but the Lockout,’ Michael continued.

‘Does it not seem a little harsh, though, locking them out of work? How can they earn a living?’

‘Whose side are you on – some pretty, violent girl?’

Maybe, Daniel thought.

‘Look, the employers only did what the strikers did, banded together. They took no nonsense. You have to be tough. It’s the only thing these people understand.’

Daniel detected a direct quote from Michael’s father. ‘So what will happen to the strikers?’ he asked.

‘Oh they’ll go back to work eventually,’ Michael said with certainty. ‘What choice do they have?’

Later, Daniel sat conjugating verbs at the drawing room table – or at least he should have been. He was looking at his father ensconced in his wing-backed chair by the fire, reading The Irish Times and puffing on his pipe. Normally, both these activities soothed Daniel. Not this evening.

‘Have any lawyers gone out on strike, Father?’

He lowered his newspaper and laughed. ‘The very idea! Strikes are a tool of the working classes, Daniel. Nothing whatsoever to do with us.’ He returned to the newspaper.

‘What are their conditions like, Father, the working classes?’

Down came The Irish Times, once more. His father frowned. ‘Have you finished your studies, Daniel?’

‘Yes, Father.’

Mister Healy folded his paper. He puffed on his pipe as if trying to decide where best to start.

‘Their conditions are no more or no less than they deserve. What you must understand is that we are a nation of uneducated. We lack a skilled workforce. And what we lack in skills, we make up for in drink. Mark my words. There is nothing like alcohol to take the drive from a man.’

‘Why do the workers not become skilled, Father?’

Mister Healy pointed his pipe at his son. ‘Now, there, is a question. Why, indeed?’ He seemed delighted with himself.

There had to be more to it than that, Daniel thought. The girl had spoken – so passionately – of unfairness. What did she know that Daniel’s father did not? Was her own father a striker? Daniel doubted it, though, given that her uniform was from one of the most expensive secondary schools in the country. What was her motivation, then, this – pretty, violent – girl he couldn’t get out of his head? And what was his own? For it was more than curiosity that had him dreaming that, one day, he would walk with her to the end of the pier at Kingstown, take her in his arms and kiss her.

two

Maggie

The Following Day

It was the worst day of the year. Maggie’s father’s anniversary never got easier. Her mother cooked his favourite meal, bacon and cabbage. And they sat down to dinner.

‘Bless us oh Lord and these, thy gifts, which of thy bounty we are about to receive through Christ our Lord, Amen,’ her mother prayed.

Maggie and her brothers, Tom and David, joined in on the ‘Amen.’

‘We’ll take a moment of silence to remember Father, each of us in our own way.’

Maggie, fearing that there would not be time to say to her father all that she needed to, began in a rush inside her head. ‘Father, I know what you asked and I’m doing all I can to make a difference but I’m only me. None of the girls at school care. They just think me odd. They don’t believe me that people are starving. They just think the strikes a nuisance. I know I shouldn’t have punched that boy but sometimes I get so frustrated. If it’s any comfort, I crucified my hand….’

A throat cleared.

‘Tom!’ their mother admonished.

Maggie opened her eyes.

They were waiting for her.

‘I’m sorry.’

‘It’s all right, love,’ her mother said.

‘It isn’t as if we’re hungry.’ Tom loved his sarcasm.

‘Leave her be,’ David said to his older brother.

Maggie lifted her knife and fork so that they could start. Then, she simply moved the food around on her plate. How could she eat his favourite meal without him? How could she eat at all when on this day seven years ago, she had jumped and left him behind. It was so silent without him. More than that, it was as if there was a hole where he should have been, a hole she wanted nothing else to fill. She knew that the others felt the same no matter how hungry they pretended to be. Their silence was proof of it.

She looked at her little family. Her mother, though delicate in appearance, was the rock that had kept them going, moving forward when it seemed that their world had stopped. She had returned to teaching, managed a home without servants and still found time to help others. But it was her love of her children, her understanding of each of their needs that Maggie appreciated most. She was the one who quelled Tom’s rage, who answered all their ‘whys’, who hid her own grief – for them.

Beside her,

Tom, at eighteen, resembled a man. As restless as a wind, he longed to be out bringing in a wage and righting every injustice in the world. If Tom had been an emotion it would have been rage. David, on the other hand, would have been love. He was the type of person that would make a flower grow just because the flower wanted to please him. He was like the sun, warming everyone with his gaze. He helped their mother most, and studied hardest, wanting to do what their father had asked – to get a good education.

Maggie wished that she was more like David but knew herself to be more like Tom. She too wanted a good education and worked hard for it but it was her need to right the injustices she saw everywhere that drove her. She would make a difference. Most days it felt possible. Today, she just felt tired. She wanted the hole gone, just for this one meal, to have him at the table, raging about Ireland’s history then softening into a story about boys becoming swans. He was a lot to miss.

Tom dropped his cutlery onto his plate with a clatter and turned to his mother. ‘You should have let me go in after him! Why did you hold me back? Why?’

‘You were eleven years old!’

‘I’d have saved him!’

‘Or died trying! I couldn’t let you do that! It’s the very last thing he would have wanted!’

‘Then why didn’t you go in?’ he demanded accusingly.

‘Stop!’ David shouted. ‘Stop it!’

But their mother faced Tom. ‘Because I was willing him to walk through that door any minute and I had to keep you all safe until he did.’ She bowed her head. ‘But he didn’t walk through.’ She rose quickly and hurried from the room.

David, quiet placid David, slammed his palm on the table. ‘Why did you do that? Can’t you see that she misses him as much as us, feels as much guilt as the rest of us? For Christ sake Tom, we’ve all lost him.’

Maggie hated that she was crying. Weak people changed nothing.

The Butterfly Novels Box Set: Contemporary YA Series (And By The Way; And For Your Information; And Actually)

The Butterfly Novels Box Set: Contemporary YA Series (And By The Way; And For Your Information; And Actually) Do You Want What I Want?

Do You Want What I Want? Through The Barricades: Winner of the SCBWI SPARK Award 2017

Through The Barricades: Winner of the SCBWI SPARK Award 2017 The Whale, The Goldfish and Señor Martin: A Short Story Prequel to The Butterfly Novels

The Whale, The Goldfish and Señor Martin: A Short Story Prequel to The Butterfly Novels